Torchlight CS 175: Project in AI (in Minecraft) -- Building a Brighter Minecraft World!

Video of Torchbearer in action:

(Apologies for the slight static and muffled voice!)

Project Summary:

The Torchbearer A.I. has changed somewhat from our previous idea, in that its algorithms are not necessarily the same. Instead of randomly running down the series of coordinates given to it, hoping to find a good coordinate to jump off of, the A.I. now knows that an optimal solution is n-coordinates large; thus, it tries some (if not all) of the n-coordinate combinations to see if it can come up with an optimal solution.

The goal of the A.I. is largely the same (in a grid nXn size, place just enough torches to light up the area), but two potential new goals include:

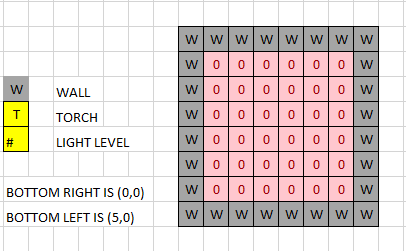

- Run the A.I. on grids with walls. This will effectively create two grids from one, as well as add an additional coordinate required to the n-coordinate optimal solution, but allows us to more accurately light up areas resembling actual rooms in Minecraft.

- Run the A.I. on non-uniform patterns – L-shapes, T-shapes, long I-shapes, U-shapes. This will give us a two additional problems to solve: non-uniform grids do not have the benefit of centralized solutions, where torches can be placed in the middle to cover the whole area; and we, as programmers, must determine what optimal solutions exist per non-uniform pattern. Once again, these patterns will more accurately resemble rooms that are actually built in Minecraft.

Of course, these goals are rather lofty, as there are many more variables to consider outside of our simple grid system (how far does the wall go to block light? Can we make multiple grids for the A.I. to accurately travel on?), and we still have some issues to iron out before then. Still, they are things to consider as we go along with the project.

Approach:

The Torchbearer A.I. determines the best locations to place torches in a grid by first determining the minimum amount of torches needed to light up the whole grid, then iterating over an n-sized combination of the valid coordinates of the grid, scoring each combination based on how many squares it left dark.

All of this is done with a brute-force method, iterating over the whole list of n-sized combinations. We are currently working on optimizing the algorithm by breaking the grids into smaller chunks (submodular optimization), but the algorithm works fine for grids sized 7 and below in terms of time taken. Given enough time, the A.I. can actually find all solutions to an nXn grid; it just takes a very long while.

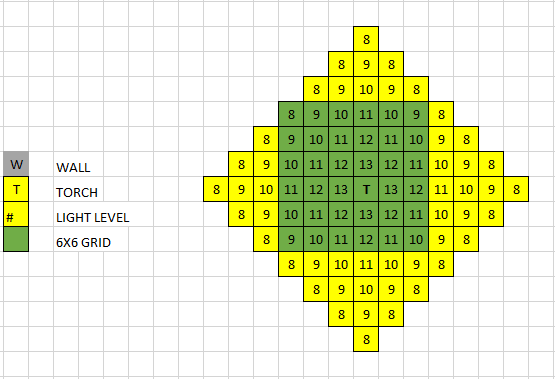

Our baseline test – a 6x6 grid – works like this:

- The minimum amount of torches is determined by the torches’ reach.

- In this case: a 6x6 grid fits into a single torch’s light.

- Mathematically, the minimum amount of torches needed is:

- int(math.floor(number/2)-2).

- In this case: 6/2 = 3; 3-2 = 1.

- This has proven true so far for 9x9 squares and below.

- The amount of available combinations (nCr) of coordinates is determined by the minimum torches needed (1) and the amount of spaces (36).

- In this case: n = 36, r = 1 -> 36 unique 1-sized combinations of coordinates. This list of coordinates is named “startingList” for the moment.

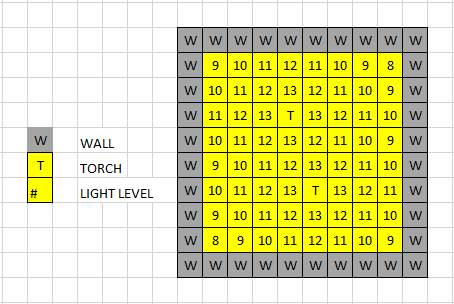

- The agent creates 6 lists, 6-size each, full of 0s to simulate the current light levels of the current test (named “currentList”).

- The list of 36 combinations are then passed to the agent, who places a torch at each coordinate in the combination per test and checks the “score” of that placement:

- First, the agent teleports to coordinate (x, z). This torch’s coordinate in the “currentList” is determined first by its z-level, then by its x-level (so blocks at z-level 1 are in currentList[1]; a block at (1, 2) is at currentList[1][2]).

- NOTE: Minecraft reads positive X going left, and positive Z going up. (Alternatively, positive X is going up, and positive Z is going right.)

- Then, the agent places a torch at its current position (x, z), in the Minecraft world.

- After placing the torch, the agent updates what the new light levels of its surroundings should be.

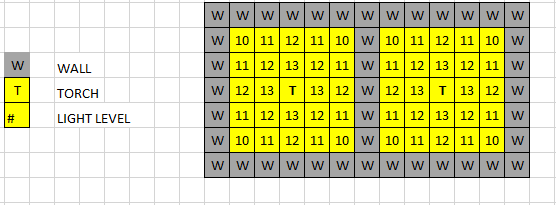

- The coordinate with the torch updates its number in “currentList” to 14 (“initialNum”).

- For each coordinate in currentList that is not that coordinate, they update based on their taxicab distance away from the torch. This distance (“tryNum”) is equal to their difference in x coordinates + their difference in z coordinates.

- An example of taxicab distance. The red, blue, and yellow lines all travel the same distance (12), while the green line is the unique solution that goes directly from point A to point B (approximately 8.49). (Image By User:Psychonaut - Created by User:Psychonaut with XFig, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=731390 )

- The new light level of that specific coordinate is equal to “initialNum - tryNum” unless said light level would be lower than it currently is.

- After placing all of its torches within the combination it is testing, the agent then “scores” the combination based on how many squares remain in the grid that have a light level of 7 or below. This score is named “dark”.

- The combination is then placed into a dictionary “scoredList”, which has a variety of numeric keys and a list value. The combination is appended to the list with key “dark”; if that key does not exist, a new key is created with its value containing the combination.

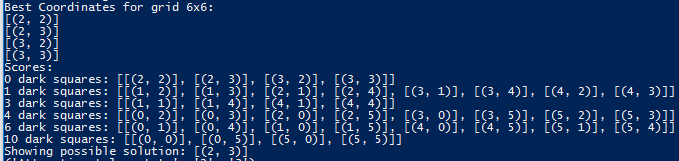

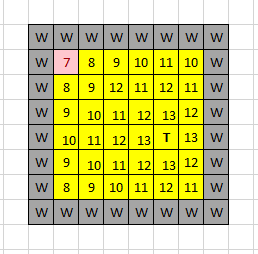

- An example of the “scoredList” would be scoredList[1] == [[(1, 2)], [(1, 3)], [(2, 1)], [(2, 4)], [(3, 1)], [(3, 4)], [(4, 2)], [(4, 3)]].

- The agent then wipes the board of all torches and begins the next test.

- First, the agent teleports to coordinate (x, z). This torch’s coordinate in the “currentList” is determined first by its z-level, then by its x-level (so blocks at z-level 1 are in currentList[1]; a block at (1, 2) is at currentList[1][2]).

- After testing and scoring each coordinate in “startingList”, the program runs over each score in “scoredList” that has a list of coordinates (or a len > 0). If that score is the lowest so far, it updates a variable “lowest” to keep track of the list.

- Finally, the program runs over the list of the lowest scoring combinations, printing each one to show the optimal combinations to place torches to light up the grid (in this case: (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 2), (3, 3)), as well as the entirety of “scoredList” for viewing purposes. The in-game agent places a combination as an example optimal solution.

Evaluation

Our evaluation goals were straightforward:

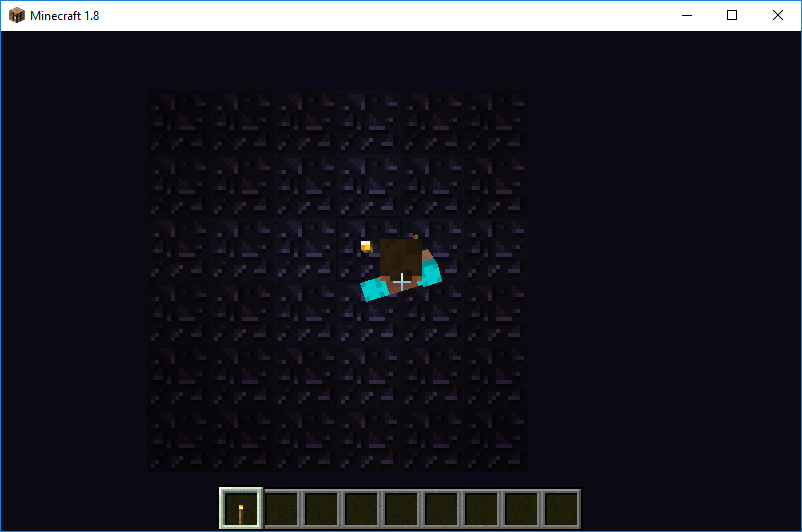

- Can the A.I. navigate a given grid?

- Can the A.I. light up that grid properly?

- Can the A.I. navigate and light up the grid in a timely manner?

By utilizing code from CS 175’s Assignment #2, we were able to set up our agent to teleport to given coordinates (x, z) easily. With the “taxicab” function, we also set up an simple way to update the light levels of a current grid if a torch was placed at coordinate (x, z). Malmo’s agent functions allowed us to simulate our grids in the Minecraft space, having the agent look down and place a torch (in Creative mode) to visually represent our light levels.

We learned quickly that while the first and second terms were easily accomplished, the third was much, much harder to achieve. The algorithm we utilize takes up vastly larger amounts of time and memory for every two increments on the nXn square:

- A 6x6 grid only checks 36 1-size combinations.

- A 7x7 grid only checks 49 1-size combinations.

- An 8x8 grid checks 2016 2-size combinations.

Eventually, our algorithm can solve that 8x8 square (in fact it is possible to solve by hand), but it will take an incredibly long time to do so (approximately an hour). Our issue is that it checks every solution and not the best ones (e.g. placing two torches directly next to each other).

While optimization is a major issue, there is no doubt that the program works. The function determining current lighting is simple, only having to iterate over nXn numbers and update them if they would grow brighter. Each test only takes about two seconds of real time, and most of that is on the agent taking a half-second to look down in the Minecraft client and Malmo’s “world_state waiting” function that is standard within Malmo projects (the line stating “while not world_state.has_mission_begun” that is in all Malmo projects).

Remaining Goals and Challenges

Our current goal is optimizing the algorithm. Mathematically the algorithm is sound, but each solution is checked one by one, which quickly becomes inefficient and time-consuming. Checking 1-sized combinations is efficient as we only have to worry about nXm positions (the m is an important distinction here, discussed below). 2-sized combinations (8x8 and 9x9) become daunting as all possible combinations become 2016 and 3240, respectively; and a 3-sized combination of a 10x10 grid has 161700 combinations to check!

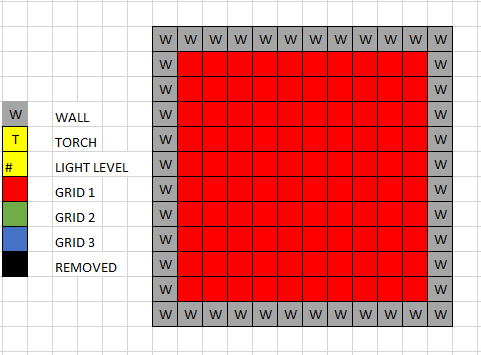

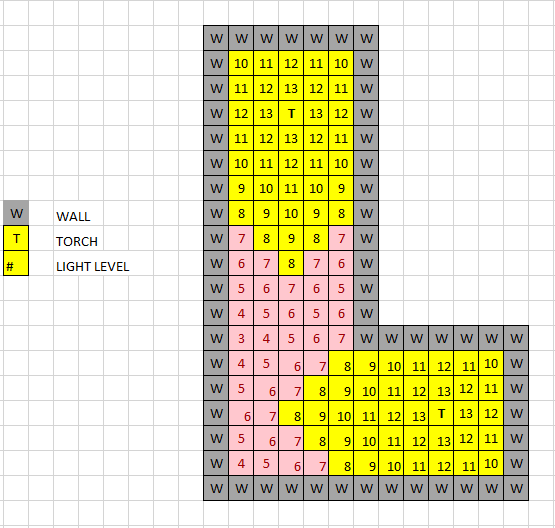

A way to break down our problem, as mentioned above, is to use submodular optimization:

- The 10x10 grid can easily be broken down if we take out one large 7x7 grid that we know is covered by the light cast from a single torch.

- This reduces the grid we have to scan from 100 positions to 51 positions, and the amount of torches to consider from 3 to 2.

- The amount of combinations in a 51C2 is 1275, a much more manageable amount compared to 161700.

- This solution can be further broken down into two rectangles (specifically 3x10 and 3x7), allowing us to only have to worry about 30 and 21 positions and to consider only 1 torch for each grid.

- 30C1 and 21C1 (30 and 21…) are even smaller compared to 1275!

This process has to be followed 3 more times (each “corner” of the grid that fits a 7x7 square), for a total of (4 * (30 + 21 + 1)) = 204 solutions to check. Much easier than 1275, and much, much easier than 161700.

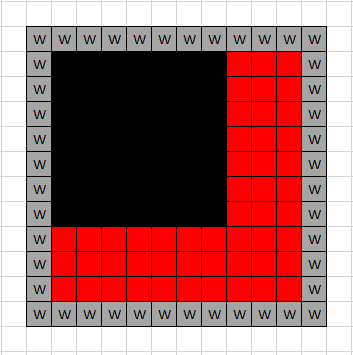

Grid 10x10:

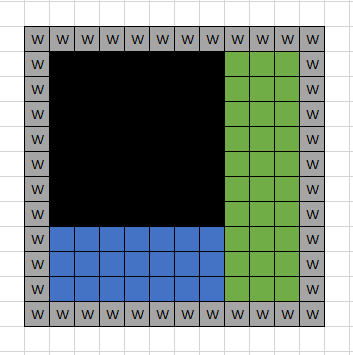

Grid 10x10 with 7x7 removed:

Grids 3x10 and 3x7:

![image for scoredList[1]](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Raustana/Torchlight/master/docs/images/scoredList1.PNG)